Alexey GROMOV

PhD in Economic Geography, Principal director on Energy Studies, Head of Energy Department, Institute for Energy and Finance e-mail: a_gromov@fief.ru

On October 14, 2020, the European Commission published an EU strategy to reduce methane emissions, Brussels, 14.10.2020 COM (2020) 663 final, prepared in accordance with the roadmap for the implementation of the European Green Deal, which provides for the development over the next few years of the foundations of a new regulatory framework in the EU for the formation of a climate-neutral European economy and energy by 2050.

Methane is the second most-impactful greenhouse gas affecting the processes of climate change on the planet afterСО2. Moreover, according to the European Environment Agency, the concentration of methane in the atmosphere has increased significantly over the past 40 years, and according to available forecasts in 2016, by the mid-2020s, it is methane that – for the first time in history – could make up a larger share of total greenhouse gas emissions than СО2. According to the IEA, despite the fact that methane remains in the atmosphere for a shorter time than CO2, the greenhouse effect from methane emissions is more than 85 times higher than from carbon dioxide at a horizon of 20 years and 30 times higher at a horizon of 100 years2.

Taking into account the ongoing reduction of own production of natural gas in the EU countries, the European Commission is paying special attention to the control and accounting of methane emissions from pipeline gas and LNG imported into the EU.

1 European Environment Agency (EEA), 2016.

2 IEA Methane Tracker Website.

In this context, the adopted strategy marks the EU’s first step in forming a new legal and regulatory environment intended to formalize and tighten the requirements for the accounting and control of methane emissions in the EU countries, including introducing norms (standards) of methane emissions for all fossil fuels (with a special focus on natural gas) sold in the EU. It is expected that the new legislation will be developed by mid-2021, and its entry into force will take place as early as 2024.

Current estimates of methane emissions

According to estimates given in a special IPCC study3, as of 2010, methane emissions accounted for 16% of total greenhouse gas emissions, having increased in absolute terms by 2.7 billion tons over the past 40 years4.

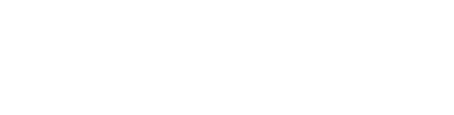

About 60% of methane emissions are of anthropogenic origin. The main sources of emissions of this gas into the atmosphere are agriculture – 45%, waste (landfills) – 20%, and the energy sector – 30% (Fig. 1). At the same time, in the energy sector itself, the bulk of methane emissions come from the oil and gas industry (54%).

At the level of individual countries and regions, the structure of sources of methane emissions can differ from global levels. Thus, in the EU, agriculture accounts for 53% of all methane emissions, and the energy sector – for 19%. In Russia, the energy sector dominates in methane emissions (76%), while agriculture accounts for only 6% of all emissions of this gas.

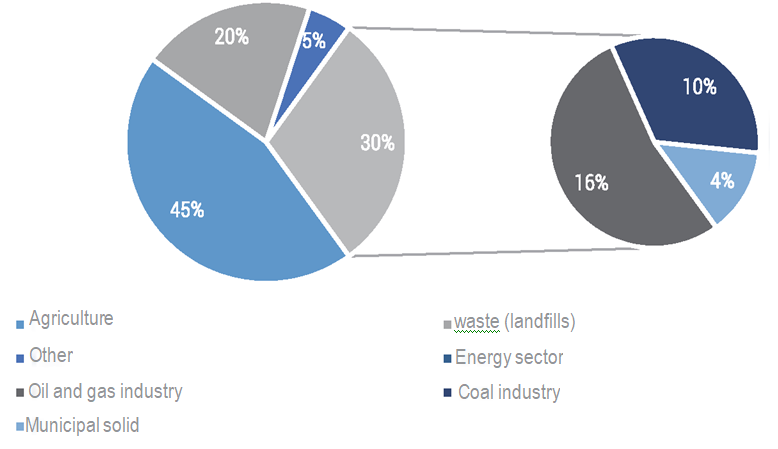

For the period from 2000 to 2017, world methane emissions increased by 20% and amounted to 8.6 billion tons of СО2-equivalent (Fig. 2).

3 The IPCC is the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

4 IPPC’s 5th Assessment Report, 2014.

Source: wallpapersafari.com

Fig. 1. Main sources of methane emissions, 2019, %

Methane is the second most-impactful greenhouse gas affecting climate changes on the planet afterСО2. By the mid-2020s, the share of methane will have exceeded that of СО2 in the volume of greenhouse gas emissions

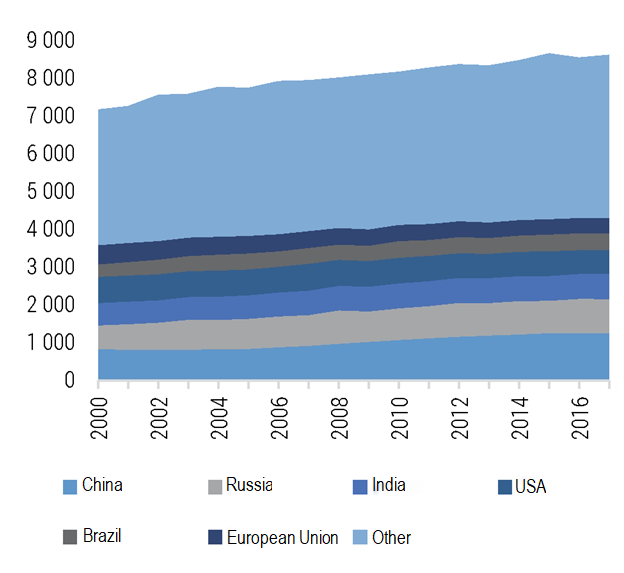

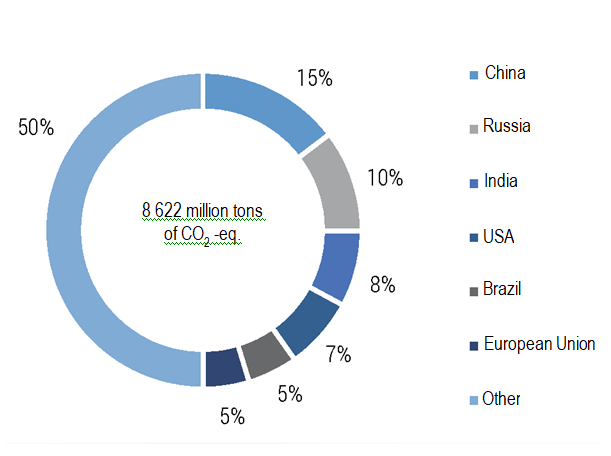

According to Climate Watch Data, at the level of individual countries and regions of the world, the main concentration of methane emissions (50%) falls on China, Russia, India, the United States, Brazil and the European Union (Fig. 3).

It should be noted that the highest-growing rates of methane emissions are in China (+52% since 2000) and in Russia (+40%), while methane emissions in the EU, on the contrary, are decreasing (-22%).

For comparison, during the same period, СО2 emissions rose by 40% in the world, in Russia, carbon dioxide emissions increased by only 2.5%, while in China, they rose 2.7 times, and decreased by 14% in the EU.

Thus, it should be recognized that the problem of methane emissions for Russia is very relevant, given its role as the largest supplier of hydrocarbons to Europe, especially in the context of the EU strategy to reduce methane emissions.

Problems of accounting for methane emissions

The world still lacks a unified methodology for assessing and accounting for methane emissions, which complicates the practical implementation of measures for their purposeful reduction, including a reduction in the oil and gas industry.

Currently, there are three categories of methane emissions from the oil and gas industry:

– controlled direct emissions of methane into the atmosphere during the extraction and processing of oil and gas;

– emissions from flaring – mainly from the flaring of associated petroleum gas (APG);

– emissions (unintentional, including accidental, leaks) during the transportation and distribution of natural gas, including emissions in expansive gas transmission systems focused on the import-export of natural gas, as well as during the liquefaction, transportation and subsequent regasification of LNG. Two methods of accounting for methane emissions are most common in the oil and gas industry: ground-based accounting and airborne methods.

Fig. 2. Dynamics of methane emissions by major countries and regions of the world, 2000-2017, million tons of СО2 -equivalent

Source: FIEF, on the basis of Climate Watch Data

Fig. 3. Largest methane emitters, 2017, %

Source: FIEF, on the basis of Climate Watch Data

The main concentration of methane emissions (50%) comes from China, Russia, India, the USA, Brazil and the EU. They’re growing most rapidly in China and Russia, while in the EU they are decreasing.

Ground-based emission accounting is based on a simple calculation of the number of gas-producing wells and their multiplication by the average annual methane emission from one well. This approach is highly dependent on the quality of the source data and the accuracy of its collection. Often, it is impossible to take into account all gas wells or take into account their status (operating or decommissioned). The average methane emission per well can vary greatly depending on the specific gas production conditions (climatic conditions, production seasonality, etc.).

Airborne methods of accounting for methane emissions through the use of UAVs (drones) make it possible to obtain more accurate information on the emissions of this gas in real time at a wider range of facilities where it may leak. However, the possibilities of aerial photography are highly dependent on good weather conditions, during which most of the measurements are taken. However, their subsequent annual averaging can significantly distort the objective reality. Also, this method of accounting for emissions often fails to allow for identifying their source.

In 2006, the IPCC developed guidelines for methane emissions accounting for certain segments of the economy and energy sector, which were updated in 2019 and recommended by the UN for application at the national level.

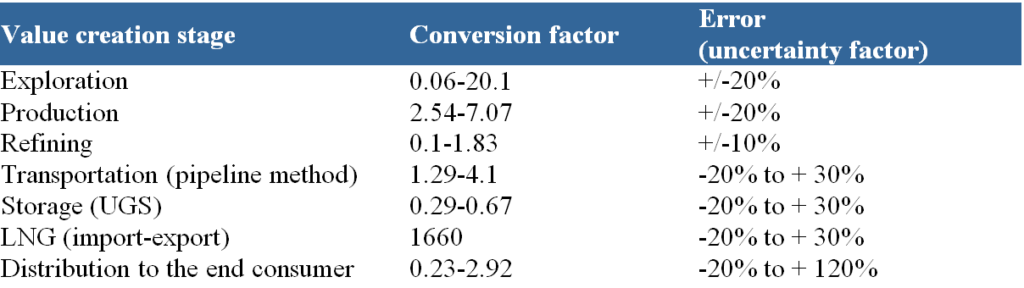

They include three possible levels (in terms of accuracy and details) for methane emissions accounting (as applied to the gas industry, in particular):

• The first level is based on the IPCC-recommended averaged conversion factors for hydrocarbon fuels in methane emissions at different stages of value creation in the gas industry (from exploration and production to final consumption).

• The second level is based on the same principles of conversion of hydrocarbon fuels in methane emissions as in level 1, but instead of averaged factors, national factors are used that take into account the country-specific nature of the oil and gas industry. For example, in Russia, Gazprom uses a conversion factor of 6.

• The third level involves the development of detailed models for methane emissions accounting at the level of individual companies.

The main disadvantages of the first level of methane emissions accounting proposed by the IPCC are attributed to the fact that all of the averaged conversion factors for hydrocarbon fuels in methane emissions are based on American data sources, in particular – data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). And this data may not always be correctly applied to other countries. The methodology also assumes maintaining a fairly high level of error in the presented conversion factors for most stages of value creation in the gas industry (+/- 20%), and for certain stages, such as the final distribution of natural gas, the level of error can reach up to +120%, which can lead to a significant distortion of the real picture of methane emissions, both downward and upward (see Table 1).

The main disadvantage of the second level of methane emissions accounting is the lack of transparency in the calculation of national conversion factors for hydrocarbon fuels in methane emissions, as well as varying degrees of detail and quality of the data that countries use to present their national factors.

The third level of accounting for methane emissions is of the greatest interest for the oil and gas industry, since detailed models for methane emissions accounting at the level of individual companies are already being actively developed and implemented in several countries around the world with the support of the intergovernmental Coalition to reduce short-lived climate pollutants (NACC) under the UN Environment Program.5 Moreover, the International Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP)6, established in 2014 under the CCAC, has developed a new Standard 2.0 for the data collection and accounting of methane emissions, which significantly improves data accuracy and detail.

The IEA has proposed a new method for methane emissions accounting based on the methane saturation indicator.

It is defined as the ratio of the mass of emissions to the mass of produced and processed fuel

In accordance with this standard: – companies participating in the partnership must report actual data on methane emissions from both operated and non-operated assets;

5 The Climate and Clean Air Coalition. URL: https://ccacoalition.org/en

6 The Oil & Gas Methane Partnership. URL: https://www.ccacoalition.org/en/activity/ccac-oil-gas-methane-partnership

Table 1. Basic averaged conversion factors for hydrocarbon fuels in methane emissions by main stages of value creation in the gas industry

Source: FIEF, on the basis of IPCC data, 2019

– reporting of methane emissions should cover all segments of the oil and gas sector where significant methane emissions can be observed;

– the scope of reporting should be expanded from the original nine main sources to all material sources of methane emissions;

– partner companies will be required to announce their own individual targets for methane emissions reductions and periodically report on progress towards these targets;

– five reporting levels have been established, with the highest requiring methane emissions to be accounted for by direct measurements for each emission source, with an indication of its location.

Companies participating in the partnership have 3 years to achieve compliance with the requirements of this standard for operating assets and 5 years for non-operating assets.

Note that currently, the partnership encompasses 62 energy companies – mainly from EU member states. Russian companies are not members of the Partnership.

The main goal of the EU strategy is to reduce methane emissions by 35-37% by 2030 compared to 2005 in three sectors of the economy: agriculture, waste management and energy.

In 2019, the IEA proposed a different methodology for methane emissions accounting within its own project – Methane Tracker – based on the methane saturation indicator (Methane Intensity) of various segments of the oil and gas business. This indicator is the ratio of the mass of methane emissions to the mass of recovered/produced/processed/distributed fossil fuels, including natural gas. This figure is calculated for 18 oil and gas business segments, based on a detailed analysis of relevant data for the United States, which then can be applied to other large oil and gas producing countries by using special scaling factors (values for the United States are taken as unit levels).

The energy sector, which accounts for 19% of the total anthropogenic methane emissions in the European Union, has the greatest potential for reducing methane emissions

In particular, for Russia, the IEA applies a scaling factor of 1.6 for gas recovery, and 2 for its transportation and distribution to the end consumer.

The advantage of this methodology is the ability to scale it to other countries, taking into account real sectoral assessments, rather than prescriptive national standards (often based on data of different quality and depth of coverage), as well as the uniformity of methodological assumptions, which simplifies cross-country comparisons for this indicator.

In fact, Methane Tracker is an independent methane monitoring tool that actually encourages those countries that think it “overestimates” their actual methane emissions to develop their own methane accounting systems and improve the quality of related statistics. At the national level, this tool is being used as an experiment by Norway.

Key provisions of the EU strategy to reduce methane emissions in the energy sector

The EU strategy to reduce methane emissions in the energy sector is an important starting point for the development of relevant European legislation, as until recently, the EU lacked a targeted methane abatement strategy, as opposed to greenhouse gas emissions in general, where there is a rather

clear regulatory framework with well-known targets for reducing total EU greenhouse gas emissions.7

The main goal of the strategy is to reduce methane emissions in the EU by 35-37% by 2030 as compared to 2005 levels.

The strategy identifies three main sectors of the EU economy (agriculture,

waste disposal and energy) as the key emitters of methane in the region for which a special regulatory policy in this area is required.

At the same time, the adopted strategy directly emphasizes that the energy sector, which accounts for 19% of the total anthropogenic methane emissions in the region (for comparison, agriculture accounts for 53%), has the greatest potential for reducing methane emissions.

Although the strategy recognizes the problem of methane leaks from both existing and abandoned coal mines as significant, the document focuses on natural gas, the world’s largest importer of which (both in the form of pipeline supplies and in the form of LNG) is the EU.

Expected changes to EU legislation

To achieve the declared goal, the strategy provides for the introduction of the following regulatory and legal requirements:

– implementation of mandatory data collection, accounting, and control of methane emissions, as well as reporting in accordance with the methodological recommendations (Standard 2.0) of the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP);

– introduction of commitments to improve systems for detecting and eliminating methane leaks at all natural gas infrastructure facilities, as well as any other infrastructure used in the production, transportation and final distribution of natural gas, including its consumption and storage;

– amendments to EU legislation to eliminate planned emissions of methane into the atmosphere and its direct combustion in the energy sector along the entire value chain of fossil fuels up to the points of its extraction.

The strategy calls for a revision of EU climate and environmental legislation, namely the EU Industrial Emissions Directive (2010),8 the European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (2006).9

It is also planned that the legal and regulatory requirements of the strategy will be taken into account in the development of the following legally-binding EU documents:

1. The Zero Pollution Action Plan (2021).

2. The third edition of the Clean Air Outlook (2022).

3. The National Emission Reduction Commitments Directive (2025).

7 In line with the EU Climate Target Plan updated in December 2020, the EU has set a target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 as compared to 1990 levels.

8 Industrial Emission Directive (IED), 2010/75/EU.

9 European Pollutant Release and Transfer Register (E-PRTR), Regulation (EC) № 166/2006.

In accordance with the requirements of the strategy, national regulators will be instructed on the need to include additional costs for detecting and eliminating methane leaks when establishing fixed-rate norms for operators of gas transmission systems in EU member states.

The international action plan of the strategy

Given the importance that the strategy attributes to methane emissions from natural gas imports into EU countries, the International Action Plan envisaged by the strategy seems especially important in the context of new risks for Russian natural gas exports to EU countries.

Thus, the strategy mentions estimates of international organizations (IEA and Carbon Limits), which directly indicate that methane emissions from imports of pipeline gas and LNG into the EU are 3-8 times higher than methane emissions associated with domestic production and the end use of natural gas by EU countries. Such high estimates of methane emissions from natural gas imports into the EU are due both to the volumes of these imports, which are several times higher than in-house gas recovery in Europe, and to the transport leg of natural gas delivery to the EU from the points of its recovery (outside the EU) to end consumers (within the EU).

The EU accounts for half of the international pipeline gas trade. When a coalition between the EU and LNG-importing countries is created in Asia, a global methane emission control tool could be created

In this regard, the strategy proposes creating a coalition of the largest natural gas importing countries with the participation of China, South Korea and Japan to coordinate efforts to reduce methane emissions.

Note that, according to BP Statistical Review (2020), in 2019, the combined share of these countries, including the EU, accounted for 58% of the international pipeline gas trade and 72% of the international LNG trade.

Russia, as the largest supplier of gas to the EU, is also the largest emitter of methane for the region; therefore, it is extremely important to estimate methane emissions from Russian gas exports.

Thus, given that the EU accounts for about half of the international trade in pipeline gas, if a coalition is successfully formed with the largest LNG-importing countries in Asia, a global tool for the accounting and control of methane emissions based on European standards could be created. And this tool would be essential – not only for pipeline gas supplies to the EU, but for the international LNG trade in its entirety.

The strategy clearly states that the EU will exert all necessary diplomatic efforts to encourage countries exporting natural gas to the EU to implement the mandatory data collection, accounting and control of methane emissions, as well as reporting in accordance with the methodological recommendations (Standard 2.0) of the international Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP).

Thus, at the international level, the strategy is focused on promoting binding EU norms and standards in the field of the accounting and control of methane emissions in all countries exporting natural gas to the EU.

At the same time, if the countries exporting natural gas to the EU ignore the calls for cooperation with the OGMP in terms of the practical application of their norms and recommendations, the European Commission will propose using the values of the averaged conversion factors for natural gas in methane emissions (the First Level of accounting for methane emissions according to the IPCC methodology) by default for those volumes of imported gas that are not equipped with systems for the monitoring and accounting of methane emissions in accordance with OGMP recommendations. And this approach will be applied as long as these countries do not implement such systems.

Moreover, in the absence of significant obligations on the part of the EU’s international partners in terms of the accounting and control of methane emissions, the European Commission reserves the right to introduce into legislation additional targets, standards or other incentives to reduce methane emissions from the fossil energy consumed and imported into Europe.

Challenges for Russian natural gas exports to the EU in the new regulatory environment

The international action plan proposed by the strategy for the practical implementation of binding EU regulations and standards in the field of accounting and control of methane emissions in all countries exporting natural gas to the EU is, in fact, an obvious attempt to extend the regulations of European legislation to third countries and creates serious regulatory and financial challenges to the long-term prospects for Russian natural gas exports to EU countries.

Key regulatory and financial risks

Thus, the strategy spells out the need to oblige all exporting-countries of natural gas in the region to implement the European standard for accounting and control over methane emissions (the so-called standard 2.0 from OGMP), regardless of whether the countries exporting natural gas to the EU apply their own standards in this area. Thus, at the first stage, the EU will ensure a uniform approach to accounting for methane emissions from all countries exporting natural gas to Europe, which already at the second stage will allow the European Union to introduce new additional requirements to reduce methane emissions by these countries, which are not formally EU members.

From the standpoint of the Institute of Energy and Finance, the main regulatory risks for the export of Russian natural gas to the EU should be recognized: the risk of non-compliance of national/corporate standards applied in Russia with the European standard, the risk of violation of confidentiality conditions and possible adjustments of existing long-term contracts for the supply of Russian gas to EU countries, the difficulties of resolving possible litigation in this area with European counterparties.

Gazprom is known as being the main exporter of Russian natural gas to EU countries. The company has its own reporting standards in terms of accounting and control over methane emissions, which may not comply with the proposed EU standard. Moreover, if we assume that the EU will use the same approach to the implementation of European regulations and standards for accounting for methane emissions that were used to regulate CO2 emissions under the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), then this would mean mandatory reporting by issuers from third countries on methane emissions, which must also be confirmed by independent assessors. The latter could significantly breach the confidentiality conditions traditionally used when concluding long-term gas contracts by Gazprom, and lead to complex and costly legal procedures for adjusting them.

It’s also important to grasp that, in addition to any legal/regulatory requirements, the lack of transparency (and compliance with the European standard) of the national/corporate system for accounting and control over methane emissions is fraught with the fact that any claims that Russian exporters could potentially bring in relation to the European requirements to reduce methane emissions would not be considered by the EU.

From the financial standpoint, the risks are also quite significant.

As already noted, if gas-exporting countries to the EU refuse to introduce European standards in the field of accounting and control over methane emissions, the strategy explicitly spells out the possibility of using average methane emissions by default. Moreover, it’s clear that the volumes of natural gas supplies from third countries to the EU exceeding the default average methane emissions set for these countries by the European Commission will be subject to additional financial sanctions (fines) within the framework of the possible future so-called “methane tax” or cross-border carbon regulation mechanism, which is already in development.

According to Eurostat for 2019, Russia accounts for almost 38% of total imports of natural gas into the EU (including LNG supplies) in the amount of more than 177 billion cubic meters.

Thus, Russia, as the largest supplier of natural gas to the EU, is at the same time the largest emitter of methane for the region; therefore, the correct assessment of its emissions from exported Russian natural gas to EU countries along the entire production chain of its value creation seems to be an extremely important task from both the political and economic perspective.

Russian pipeline gas is the most competitive on the European gas market. But if the EU introduces a tax on methane emissions, it could experience a significant price hike on the European market

Given that the overwhelming volume of natural gas exports from Russia to the EU is provided by Gazprom (except for LNG exports, which are also provided by NOVATEK), it is advisable to carefully consider the official data on methane emissions that the gas concern discloses in its materials.

According to the official data provided in the environmental report of Gazprom PJSC, at the end of 2019, greenhouse gas emissions from the company’s facilities in 2019 amounted to 117.09 mln. tons of CO2 -equivalent, where methane accounted for 28% or 32.78 mln. tons of CO2-equivalent.10

At the same time, methane emissions from Gazprom’s production facilities amounted to 0.02% of the volume of produced gas; emissions during transportation were 0.29% of the volume of transported gas, and emissions during the underground storage of gas amounted to 0.03% of the volume of gas storage.

It should also be noted that Gazprom uses the global temperature change potential across a 100-year time horizon from the Fifth Assessment Report of the IPCC as an additional metric to calculate total СО2-emissions. Thus, to reflect the emissions of fossil methane in CO2-equivalent, the national conversion factor 6 (Second Level of accounting for methane emissions according to the IPCC methodology) is applied.

In addition, Gazprom is participating in the international initiative “Guiding Principles on Reducing Methane Emissions across the Natural Gas Value Chain” and engaging a well-known auditor, i.e. KPMG, in the audit of its activities involving data collection, accounting and control over methane emissions, which independently confirms the data disclosed by the company within the framework of public environmental reporting.

However, we must emphasize that the EU strategy to reduce methane emissions is based on the methodology for collecting data and accounting for methane emissions developed by the international partnership to reduce methane emissions in the oil and gas industry, OGMP, based on the IPCC guidelines (level 3). But Gazprom is not part of this partnership and formally uses the IPCC guidelines only at level 2.

10 URL: https://www.gazprom.ru/f/posts/77/885487/gazprom- environmental-report-2019-ru.pdf

The new EU strategy to reduce methane emissions could significantly deteriorate the economics of Russian gas supplies to EU countries and negatively affect the long-term prospects for its export

Instead of a conclusion

However, even if Gazprom adopts the European methodology for methane emissions accounting imposed by the European Commission, it should be understood that over the long term, Russian pipeline gas exports will experience increasing pressure from European regulators, primarily in terms of reducing its economic competitiveness.

As is well known, Russian pipeline gas is the most competitive on the European gas market today. However, in the event of the possible introduction of a tax on methane emissions by the EU within the framework of the mechanism of cross-border carbon regulation, Russian gas could significantly rise in price on the European market, which would lead to an artificial leveling of the economics of LNG and pipeline gas supplies to the EU (methane leaks as a result of evaporation and its subsequent regasification are estimated to be significantly lower than the loss of methane during extraction and its subsequent pipeline transportation).

Thus, the new EU strategy to reduce methane emissions and its subsequent practical implementation could significantly deteriorate the economics of Russian natural gas supplies to EU countries and negatively affect the long-term prospects of Russian gas exports to this region.