Arseniy POGOSYAN

Correspondent of the Energy Policy magazine

e-mail: PogosyanAS@minenergo.gov.ru

The article describes the main trends in the development of the oil and gas complex in Africa. The author analyzed the work of Russian companies on this continent and identified the main risks for the implementation of new oil and gas projects in Africa.

Keywords: oil and gas production, growth in consumption of petroleum products, geopolitical risks.

Energy demand

If you look at the current forecasts of the United Nations (UN), a lightning fast speed of the global population growth becomes obvious. By the middle of the century, there will be 9.9 billion of us. By 2053, the number of people on the planet will have overpassed the 10 billion milestone. For comparison, in 2018 the population of the Earth was about 7.6 billion people. Moreover, in the XX century the population grew mostly in developed countries but the sign of the XXI century is a growth in the developing economies of South-East Asia and Africa. The number of inhabitants of the latter will double up to 2.5 billion and by 2100 it will already be 3 billion people, that is, a third of the total population of the planet. Today the share of the African population is only 15%. The UN believes that, for the most part, population will keep growing mainly in poorer countries south of the Sahara desert, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Ethiopia, as well as in the more prosperous South Africa.

From 1999 tо 2018, proved oil reserves of African countries increased from 84.7 bln bbl to 125.7 bln bbl or 7.5 % of global reserves

At the same time, in the late XX and early XXI century African countries have shown that they have enough energy resources, otherwise they wouldn’t be able to sustain the life of such a large population. According to British BP1, proved oil reserves of African countries increased from 84.7 to 125.7 billion barrels from 1999 to 2018, accounting for up to 7.5% of global oil reserves. In general, over the past 100 years Africa has managed to significantly improve its energy security and acquire new resources for economic development.

Africa

is where a unique situation is emerging when a certain country can be among the

world leaders in oil or gas production, but at the same time a significant part

of its population does not have an uninterrupted supply of electric

power.

At the same time, according to BP, the

demand for energy among the population provided with energy is growing by 2-3

percentage points per annum, having changed from 3.32 to 4.1 million barrels

per day from 1999 to 2019. This is at least 2 times higher than the worldwide

average rate (1.3 percentage points). This fact poses an ambitious problem for

the leaders of African nations and external investors to find new available

resources in order to balance supply and demand in countries to lead by

population growth in the future.

According to analysts, by 2050 the region has every chance to close the gap between the consumption (3% on the global scale) and production (12% on the global scale) of energy. African countries will have to annually increase the rates of drilling and oil and gas production so as not to face a dependency on imported energy resources in one day.

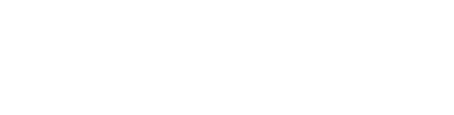

The energy balance of power sources, say, of Russia and African countries taken together is quite similar. Natural gas in Russia accounts for up to 48% of all the generation, while in Africa this share is 42%. The situation with coal is similar: 19% and 23%, respectively (see Table 1).

Source: data of McKinsey

It is natural gas that the International Energy Agency and the US Energy Information Agency attach the leading role as the most promising, fastest growing source of primary energy for the period up to 2040. Agencies expect that the demand for natural gas might grow from 43% to 57%. The demand will mainly grow in developing economies of Asia, Africa, Latin America and the Middle East. According to the calculations of RAS (Russian Academy of Science) IES (Institute for Energy studies), African countries will have to increase the total production of liquid hydrocarbons by 50 million tons in total by 2040 (see Table 1), provided that the existing levels of oil exports to China (79.5 million tons in 2019) and India (30.2 million tons in 2019) remain. For comparison, only African countries (mainly Libya, Nigeria, Angola, Algeria and Sudan) produce 399 million tons of oil annually, averaging at 8.1 million barrels per day. Of these, the lion’s share, 6.8 million barrels per day, is exported. That’s more than 10% of the global daily level. Oil volumes remaining on the domestic market are actually subsidized by these exports. Domestic retail prices for gasoline and diesel, where it is basically available, often tend to be close to the prime cost of the product.

In fact, a low development of the oil refining infrastructure is one of the typical features of almost every producing country in Africa. Most of the refineries there were built in the 1960s and 1970s and, as a rule, have not been upgraded with new secondary installations since. Poor equipment of processing facilities does not allow a full utilization of existing plants, therefore the average load rate in the region does not exceed 60%. At the same time, the region as a whole is characterized by a persistent shortage of petroleum product supply, despite the vast resource base and oil exports.

Source: wognews.net

OIL out LUK

At the moment, almost every more or less large oil producer in Africa faces the difficult task of attracting new investments into their production under the conditions of relatively low hydrocarbon prices, declining production and limited consumption caused by the coronavirus pandemic. According to BP, the region has lost 2.1% of annual crude oil production over the past 10 years with a reduction in the yield from 9.92 to 8.4 million barrels per day. This trend only escalates the competition between countries for an investor, as only Congo has a stable production growth (from 276 to 339 thousand barrels per day) out of the 12 oil-producing states monitored by BP and oil production in 5 countries is in steady decline (Algeria, Angola, Egypt, Equatorial Guinea and Tunisia).

They can’t develop the production using their our own means and technologies. Africa remains one of the few continents on Earth where resources of the national oil companies are insufficient for this. The same factor once made possible a massive arrival of large multinational companies such as ExxonMobil (assets mainly concentrated in Nigeria) and Royall Dutch Shell (assets in Nigeria, Egypt, Tanzania). The explosive growth in production and new projects in the 2000s–2010s changed to a decline in interest and the abandonment of projects already under development in 2019–2020. Today, American ExxonMobil and Chevron are looking for new owners for a part of their assets in Nigeria and Marathon Oil and Occidental Petroleum are searching new partners for shares in Libyan projects.

Russian LUKOIL is one of the “oldies” and pioneers of the African oil and gas business. Due to the difficulties in expanding the resource base in Russia, the company started to actively buy shares in foreign offshore projects back at the dawn of its operation.

In the mid-1990s, when LUKOIL first entered the continent, it was believed that the most promising projects were in the western part of Africa: in the Gulf of Guinea and further south along the deep-marine shelf of the country’s shore. Having started from shallow waters of Egypt in cooperation with the large Italian Eni on the Meleiha project, the company found sites for itself in Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Congo, Nigeria and Ghana already in the 2000s. The “shale revolution” in the United States and the subsequent collapse of oil prices exposed weaknesses of the projects and forced LUKOIL to make a quicker investment decision regarding work on them. In 2015, the company showed a loss on dry wells for 2014 in the amount of 9 billion rubles and promptly abandoned projects in Sierra Leone (block SL-5-11) and on the Ivory Coast shelf (a total of five blocks in the Gulf of Guinea). In parallel, the American Panatlantic had left the shelf of these and other countries, and then completely closed. Exploration, indirectly related to the management of LUKOIL, we can only guess about its losses. The beginning exodus from the African continent fueled rumors about both the reform of offshore production in Russia and the sale of LUKOIL’s Italian refinery ISAB that is also focused on crude products from Africa.

Source: mozambiqueoilmining.com

Taught by bitter experience, the “water extraction” company of Vagit Alekperov (as he himself called it in an interview at the end of 2019) tightened its approach to the selection of fields, actually abandoning its participation in risky projects and deciding to enter well-studied sites only, in partnership with experienced majors.

At the moment, the announced exit of ExxonMobil from Africa in favor of the shale projects of the USA and Canada becomes another chance for LUKOIL to gain a foothold in the local market and potentially become a major investor into oil and gas projects on the continent. Now, according to V. Alekperov, the company is considering for itself the already yielding Zafiro field (90 thousand barrels per day) in Equatorial Guinea and a number of gas projects owned by ExxonMobil. LUKOIL signed a basic agreement on cooperation with the country’s authorities back at the Russia-Africa summit in 2019.

In fact, the Vagit Alekperov’s company began to reassemble its “African package”. The latest purchases here include 25% in the Marine XII project in Congo for $ 768 million, and a 40% stake in the RSSD (Rufisque, Sangomar and Sangomar Deep) project in the Republic of Senegal for $ 300 million. The company still has two facilities in Ghana within the framework of a deepwater project in the Tano block (Deepwater Tano/Cape Three Points), which received the first oil inflows in 2018, as well as the Cameroon project Etinde (LUKOIL’s share in the project is more than 30%), which the company entered at the end of its first round of the African campaign in 2015 for $200 million. The investment decision regarding this project will not be made until 2021. By the way, besides Zafiro, the Russian company has already entered in Equatorial Guinea into a project for EG-27 block development on the country’s shelf, involving the construction of a floating LNG plant.

The ambitious LUKOIL expects to expand its business in Nigeria, the largest oil producer on the continent. At the end of November 2019, the company increased its stake in geological exploration block 132 from 18 to 40%, while continuing to work at block 140 simultaneously (the total reserves of the two blocks are estimated at 3.3 billion barrels of oil) and hold negotiations with Eni on entering the existing Aba project.

There is a unique situation in Africa where countries may rank among world leaders in production of oil or gas but at the same time a significant portion of their population is deficient in energy

It is symbolic that LUKOIL kept its first purchase in Egypt, the WEEM, WEEM Extension and Meleiha projects, and keeps developing them in accordance with the agreement.

Participation of Russian companies in the Egyptian oil industry expanded at the end of 2019 when Zarubezhneft signed its first African Production Sharing Agreement for the South East Ras El Ush (SEREU) and East Gebel El Zeit (EGZ) blocks offshore Egypt.

In the future, according to sources, Zarubezhneft does not mind considering projects in the Republic of Congo, where the oil product pipeline Pointe Noire – Ye – Oyo – Ouesso is already under construction with the participation of the Russian GK RusGazEngineering JSC.

There are oil prospects in South Africa that began in 2018 a cooperation with Rosgeologia JSC on exploration and development of the E-CB and E-BK parts within the 9th southern shelf block.

Liquefied hopes

But if the oil production is still increasing solely with the aim of increasing supplies to foreign markets, the production of blue fuel is focused primarily on the domestic market. It is assumed that the demand for gas will be warranted by the developed countries of northern and central Africa, where an increase in power consumption is expected. According to BP, gas consumption in Africa has grown more than 1.5 times over the past 10 years, from 95 to 150 billion cubic meters per year. During the same time, the Africans were also able to significantly increase their proved reserves from 11 to 14.9 trillion cubic meters at the end of 2019. However, production dynamics is gradually starting to lag behind the demand. Over the past 10 years, it has grown by only a quarter from 192 to 238 billion cubic meters.

At the same time, the export of African pipeline gas under competition with Russian gas in the European market decreased by almost 40% between 2009 and 2019. Due to the volatility in oil prices and increased competition with “freedom molecules” from the United States, as well as with Russia, the export of liquefied gas also remained unstable and actually grew only slightly – from 56 million tons in 2009 to 61.2 million tons in the last year.

Natural gas reserves in Africa, according to the International Energy Agency, amount to 487.8 trillion cubic meters2, while natural gas production accounts for up to 6.1% on the global scale.

In 2019, investments into new gas production projects hit the $ 103 billion mark. However, the overwhelming part of the funds will probably be spent on recovery, cleaning and transportation of associated gas that is still being flared most often, as it is cheaper than exploring a new gas project on a deep-marine shelf.

Algeria is rightfully considered to be the gas-richest country in Africa. This country is the largest African exporter of pipeline gas to Europe having a share of 1/5 of total gas import. As of the beginning of 2018, proved reserves of natural gas in Algeria were as high as 4.34 trillion cubic meters. Over the last year, this country has been actively attracting foreign companies to work in its hydrocarbon sector, which is supported by permanent production growth, which, by the fact, no other major gas-producing country on the continent can boast of. At the end of 2019, Algeria has changed laws to facilitate access to natural resources because in recent years the investments decreased due to bureaucratic complexity.

Source: stockinfocus.ru

Gazprom is an old partner of Sonatrach, a local state-owned company that participates in all projects of foreign companies in the country as a matter of law. The national Algerian company conducts exploration activities with Gazprom in the El Assel area in the Berkin oil-and-gas basin. Also, Rosneft is involved that won the tender for hydrocarbon exploration in Algeria together with Stroytransgaz as far back as in 2001. Algeria has signed memorandums on cooperation with all Russian major companies. This openness is reasonably explainable: the Algerian economy is largely based on export of hydrocarbons, 97% of export revenue is received from hydrocarbons. With explored oil reserves of 1.5 bln tons, Algeria is the fourth largest country in the region. However, the production is mainly provided by old fields and its level decreases gradually. Today it is less than 61 mln tons per annum, so the country bets on the gas.

By the way, it was Algeria that became the first country in the world to export LNG in 1964. Today Algeria produces LNG on 14 processing trains at four plants with a total capacity of 34.4 billion cubic meters per annum.

The last investment decisions taken in Nigeria, Mozambique, Egypt, and in other countries count in favor of LNG. Liquefied gas is considered as one of top-priority for the development of fuel and energy sector in Africa. Nigeria, along with Algeria and Egypt, is the main source of gas (49 bln cub. m, producing up to half of the total LNG exported from the continent (29 mln. tons in the total export amounted to 61 mln. tons in 2019). The potential of Nigerian LNG was noticed by Gazprom at the right time – within the period from 2010 to 2015 its trading subsidiary purchased 35 lots of Nigerian LNG with a consolidated volume of 2.1 mln. tons. Nigeria has extensive capabilities to increase these supplies. As of the beginning of 2019, proved reserves of natural gas in the country were as high as 5.35 trillion cubic meters. It is the top position in Africa and the world’s tenth largest reserves.

A probable competitor of Nigeria in this market is economically poorer Mozambique. Year 2010 became a turning point in the history of this country when Anadarko, an American oil and gas company, and Italian Eni discovered huge reserves of natural gas at the country’s deep-marine shelf. This raised Mozambique in a jiff to the 14-th line in the list of countries with largest gas reserves in the world. Its biggest gas field was named Prosperidade (Prosperity) with 29 trillion cubic meters of the blue fuel. It is expected that from 2022 gas from this field will be liquefied to LNG and exported to neighboring countries of the continent. According to the Energy Center of Skolkovo Business School, the cost of liquefaction here will be lower than, for example, in new Australian projects.

Russian Rosneft plans to occupy its place in the history of African LNG market development. “The company rates Africa as one of its three future oil and gas hubs”, said to “Izvestiya” in June, 2016 Christopher Einchcomb, Deputy Chief Geologist of Rosneft, who is in charge for upstream projects support. However, the company has not succeeded in finding a suitable project for investment so far. EG-27 block at the shelf of Equatorial Guinea might be a good choice, but the auction was won by LUKOIL. Today the company already has a 12-year contract for LNG supply to Ghana with a volume of 1.7 mln tons annually, but no source for the supply is found near Ghana up to now. It was previously expected that Rosneft can practice LNG export using its joint gas project with Eni at Zohr field in Egypt, which is the largest field in the Mediterranean region (reserves estimated as exceeding 850 bln. cubic meters of gas). However, the decrease in gas production within the country makes all the gas to be directed to the domestic market so far.

“Pitfalls” of the Gulf

Increased interest of African countries in Russia is reasonably explainable: the shale “renaissance” has weakened western investments to a significant extent, while disappointment in the Chinese who remain major foreign investors in the African economy is only growing. But opposed to Chinese companies having inexpensive credit resources to invest in doubtful African projects, Russian companies, bearing in mind the experience of LUKOIL and a number of intergovernmental negotiations, become more careful.

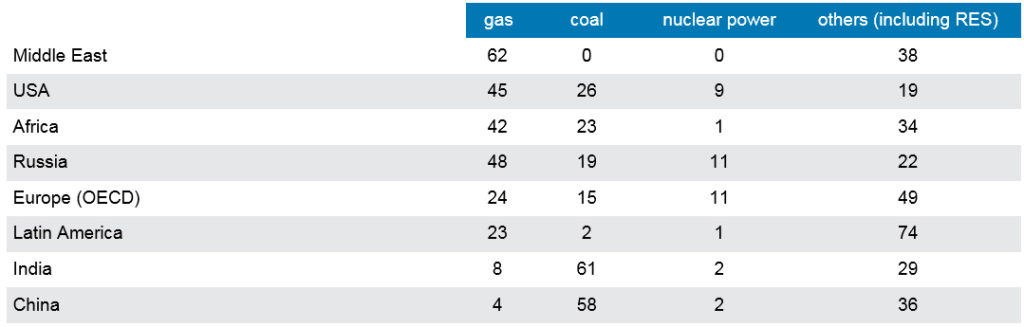

The most common problem when entering the African market is tax conditions and royalties for a project. Difficulties in agreeing royalty and contract terms were one of the reasons behind Gazprom’s withdrawal from promising projects in Algeria at the El Assel site where the company discovered two oil fields and two gas condensate fields. Typically, the cost of exploring and acquiring mining rights and not production CAPEX constitutes a major portion of the expenses for “entering” an African project (see Figure 1). In this context, the lack of skilled and technical workers to meet the requirements of the governments of East African states for local workforce involvement in project implementation is not so important.

* project closed According toRosgeologia

Another reason behind a frequent lack of information on a project, including public projects, is African authorities simply dragging out negotiations, trying to “sell” a poorly explored project instead of negotiating on more explored projects, among others, or on developing mature fields, according to a source in one of the companies. Sometimes local authorities simply stop communicating or participating in talks, the source adds. In such a case the partnership was ruptured, even if an intergovernmental agreement featuring a joint venture creation had already been signed between the countries. There were also cases when the authorities delayed payments under the already registered concession for the operator, which did not inspire hope for a continued successful cooperation either.

Thus, a consortium of Rostec, Telconet Capital, VTB Capital, Tatneft and South Korean GS Engineering & Construction won a tender in 2015 for the construction of the first oil refinery in Uganda with a capacity of 3 million tons per year. A year later, the consortium was forced to abandon the project due to the unwillingness of the Ugandan government to fulfill its tender obligations.

However, no one can guarantee that the current or new authorities won’t come up with tax claims against the concessionaire or production license owner as part of an unexpected anti-corruption investigation at some point, as it happened, for example, in Angola with the Gazpromneft subsidiary Serbian NIS in 2013–2014.

But the most common risks, the ones that hardly anyone can insure you against, are a coup d’etat or a war with neighboring state. Thus, oil production in, and export from Libya have been partially disrupted since the military coup of 2011. In the context of these news, the oil price at the end of September fell to $ 40 per barrel. Relations with Russian oil workers also fell victim to an armed conflict. Gazpromneft has already abandoned a project in Algeria and Tatneft, which has 4 contract areas in the country, still cannot return its workers to the projects. For example, country’s proximity to a military conflict is preventing a full-scale cooperation between Russia and Sudan, although private Russian investors were ready to build a plant for associated petroleum gas processing there. Nevertheless, compared to other oil and gas markets, it is African market that remains the least studied and promising, as well as closest to the future epicenter of hydrocarbon consumption. Since no large coal deposits left on the continent, there is no doubt that the share of oil and gas in the region’s energy balance will keep growing. The competition for these hydrocarbon resources and for the consumer has already begun. As the prices remain relatively low, a window of opportunity is opening for Russia right now to overtake the same China seeking to stake out a good source of energy for the needs of its economy. Today, Russia is head and shoulders above the United States and China in the nuclear sphere on this field, building one nuclear power plant and having agreed to elaborate several other NPP projects3 in Africa. With due care and preservation of political ties between countries at the highest level, Russia can really secure the position of leading operator in the oil and gas future of Africa.