Elena ANANYKINA

Senior Analytical Director,

Infrastructure Ratings S&P Global Ratings

e-mail: elena.anankina@spglobal.com

СВАМ: waiting for clarity by mid-2021

As part of the Green Deal, the European Union plans to approve a carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) by the end of Q2 2021 and introduce it from 2023. The exact arrangement is still unknown, but it’s clear that it must comply with WTO rules and the EU’s international obligations. In all probability, importers will be included in the European Emissions Trading System (ETS). Notwithstanding the debate over whether this mechanism is protectionist or environmental, it is clear that the likelihood of its emergence is very high.

According to preliminary estimates by BCG and KPMG, made in mid-2020, the total burden of Russian exporters could amount to 3-6 billion euros per year.

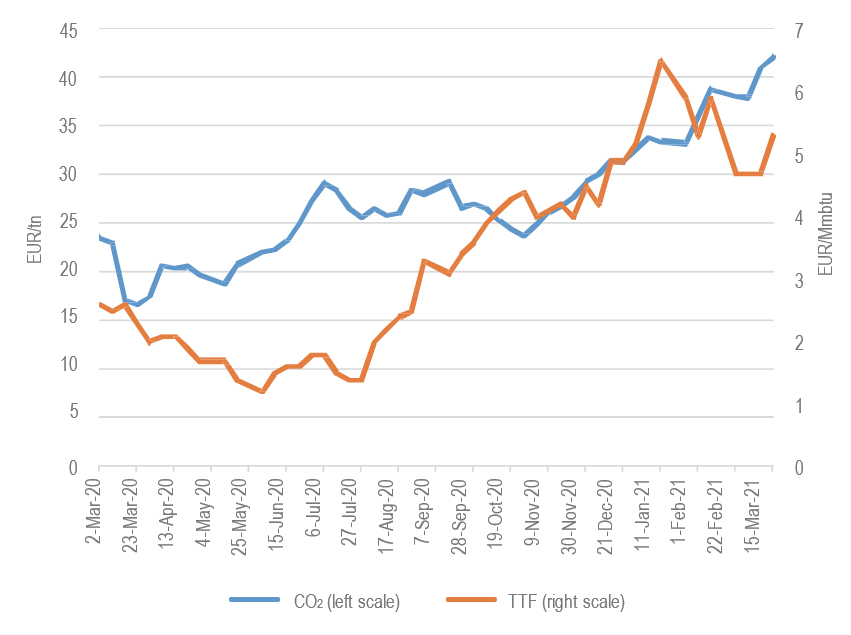

According to European Commission estimates, the total amount collected from importers from different countries could be 5-14 billion euros per year. Since mid-2020, the price of carbon emissions in Europe has risen from €30 to over €40 per ton, and the European Parliament has recommended expanding the list of paying industries. It is not yet possible to estimate the exact amount of losses of Russian companies, since some of the most important details of the CBAM mechanism remain unknown, namely:

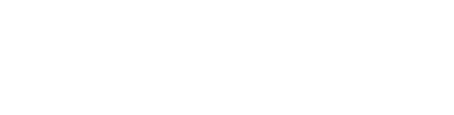

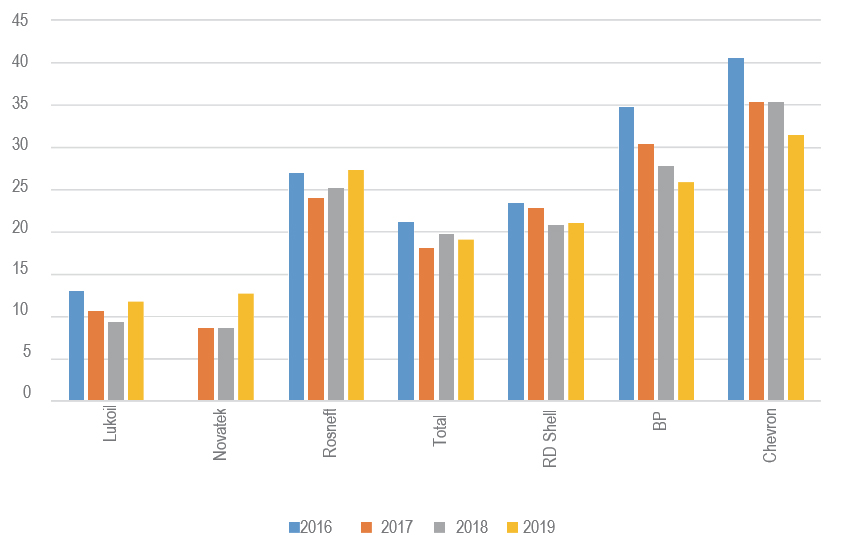

- Methodology for calculating and verifying the carbon footprint of companies. For Russian companies, of particular importance is what kind of emissions coverage (Fig. 1, 2, 3) is expected to be used, how emissions in complex supply chains are to be tracked and what principle of accounting for electricity consumption can be used: geographic (average emissions in the network) or market (emissions from electricity purchased by the company, for example – under bilateral agreements), as well as which offsets and investments in environmental initiatives can reduce the amount of the payment. According to the European Parliament statement of March 2021, the EU intends to take into account direct and indirect emissions as much as possible according to “the emitter pays” principle in order to avoid carbon leakage to countries with less strict regulation and counterparties with less strict accounting, as well as to encourage companies around the world to reduce their carbon footprint. In practice, however, not all companies participating in complex international supply chains are ready to provide reliable information on their emissions, so simplifications and averaging are inevitable. In addition, it is not yet clear which measures to reduce carbon footprint will help reduce the tax and how to certify them: whether the purchase of carbon permits will be taken into account (and which ones), direct contracts with low-carbon energy suppliers (and which ones), carbon capture and storage, investments in reforestation and other climate projects, etc.

- The exact list of paying industries. So far, it is proposed to introduce a carbon tax for the most energy-intensive industries, including the production of electricity, steel, cement, aluminum, petroleum products, paper, glass, chemicals and fertilizers. However, there is no guarantee that the list of paying industries will not be changed at the last moment. It is also not clear how to account for emissions in long production chains, where not all participants keep the appropriate accounting. In addition, introduction of the tax could affect competition between substitute goods, for example – between metals, to which the tax will apply, and plastics, to which it is unlikely to apply at the initial stage.

- Free emission quotas. After heated debate, the European Parliament is inclined to continue the practice of granting free quotas to European producers during the transition period. This places producers from other countries on an uneven footing. If they are not provided with similar quotas, it is not entirely clear how this tax mechanism is consistent with WTO rules.

Finally, the amount of payments will depend on the cost of carbon emissions after the introduction of the carbon tax. In recent months, the cost of emissions has been rising, but still remains below the level that would provide incentives to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, according to most experts (IMF, World Bank, etc.).

Exports from countries where adequate national carbon pricing mechanisms exist could be exempt from the carbon tax. Russia is discussing the possibility of introducing payments for greenhouse gas emissions, in particular – within the framework of a regional experiment on Sakhalin. This would make it possible to leave funds within Russia, including for financing climate and environmental initiatives in the regions. But whether the domestic Russian payment will be recognized as an exemption

from the European carbon tax is still unknown.

Source: dp.ru

Why won’t CBAM kill Russian exports?

Of course, CBAM will significantly reduce the profit from Russian exports. Nevertheless, in our opinion, this blow will not be critical for Russian exporters in the coming years:

- according to published reports, the emission figures of Russian exporters (in particular, oil and gas and steel companies) are approximately at the same level as those of international competitors. However, it’s worth noting that emissions data from various international sources (Edgar, IEA) differ significantly, particularly with regard to methane emissions, whose greenhouse effect is 28 times greater than that of carbon dioxide. This further underscores the need to apply harmonized emissions reporting standards;

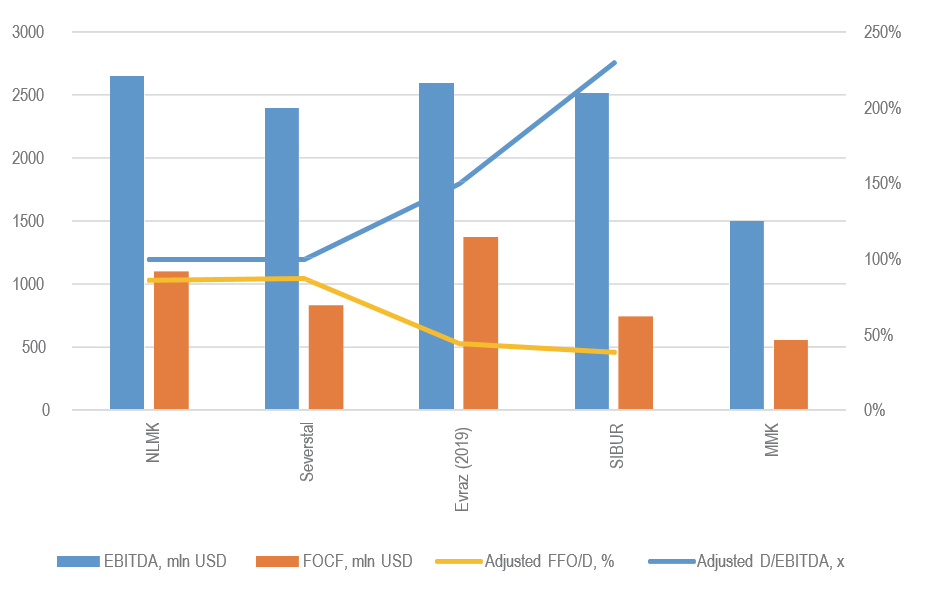

- many Russian exporters in the metallurgical, mining, and fuel and energy industries are large companies with a significant margin of financial strength. If the preliminary estimates of the payment size are close to the truth, the amount of transcarbon levy would be relatively small for them, given the size of their EBITDA, free cash flow, and moderate debt burden;

- the price of carbon emissions could affect commodity prices. As is well known, the distribution of the tax burden between the supplier and the buyer depends on the elasticity of supply and demand. In particular, in 2021, the increase in the price of ETS in Europe was accompanied by an increase in the price of natural gas;

- Russian companies have opportunities to optimize their actual or at least reported carbon footprint, depending on the adopted methodology for calculating the carbon levy (this is discussed below).

CBAM has spurred the development of ESG regulation in Russia

After the ratification of the Paris Agreement in September 2019, the development of the ESG regulatory framework has intensified in Russia. Obviously, the threat of CBAM has become one of the important catalysts for this process. A draft low-carbon development strategy, draft laws on climate projects and on carbon turnover, draft national green taxonomy and green finance principles have been prepared. The possibilities of introducing carbon payments within Russia are being discussed. The Central Bank has published recommendations on ESG for market players, standards for issuing green bonds, recommendations for insurance companies related to climate risks accounting. Russian projects are much less strict in comparison with the regulatory framework of many other countries. For example, the Russian green taxonomy project includes a shift from coal to gas and the use of NGV fuel; the decarbonization strategy is aimed at reducing emissions by increasing efficiency with a minimum contribution of renewable generation. By comparison, the current European green taxonomy project does not effectively treat gas as being green, although discussions have recently intensified about the possibility of including some gas projects as transitional if they achieve a significant reduction in carbon footprint. In Russia, the official rhetoric is changing very carefully, and this is quite natural: it is not easy to find a compromise between the interests of large companies and domestic energy consumers, between the monetization of Russia’s vast natural resources and the need to participate in the fight against climate change, between the reliability and cost of energy supply, on the one hand, and reducing emissions on the other.

Source: Dyshlyuk/ Depositphotos.com

Exporters ahead

Large Russian companies, primarily exporters or those that interact with foreign investors, have long felt pressure from international institutions and end consumers. Therefore, it is not surprising that they’re developing their own ESG strategies and often going beyond the requirements of the existing regulatory framework in Russia, which are not too strict by international standards.

Most large Russian companies with S&P Global Ratings have published sustainability reports or comprehensive reports on environmental, social and governance factors for several years. Many major players are joining international initiatives related to ESG, such as the global environmental disclosure system “Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP)” (Gazprom, LUKOIL, NLMK, Norilsk Nickel, MTS, Rosseti, etc.) and the international partnership “Guiding Principles on Reducing Methane Emissions” (Gazprom, Rosneft, NOVATEK). Many companies are adopting their own ESG targets, including targets for emissions reduction. In many cases, efficiency gains through normal operating and capital expenditures can also help to reduce emissions (for example, reducing loss in power systems).

In recent months, several Russian companies have announced the withdrawal or sale of business units with the highest levels of environmental pollution. In particular, Evraz is considering the possibility of detaching its coal assets. This practice does not fundamentally differ from the practice of comparable international companies and improves reporting indicators; however, it does not reduce the total volume of emissions, but simply drives them outside the consolidation perimeter.

Not just risks, but also opportunities

In addition to the obvious costs and risks, CBAM could open up new opportunities for companies with rather flexible strategies. Here are some examples.

- RES. As of today, the development of renewable energy in Russia is mainly supported by the RES CDA arrangement, which provides a guaranteed return on investment. As a rule, the cost of renewable energy sources in the 1st and 2nd price zones is currently higher than traditional thermal energy, but at the latest auctions, renewable sources have already been approaching coal power stations in terms of their declared one-part electricity price. If the price of carbon emissions for large industrial consumers actually becomes positive, this may further increase the economic attractiveness of a number of renewable energy projects, in particular – in-house generation at large exporting enterprises, depending on the resources of the sun, wind and the cost of traditional energy in the regions where their production facilities are located.

- Carbon dioxide capture, storage and utilization technology. Russia has enormous geological potential for the application of these technologies. The return on investment in capture and storage depends on the price of carbon and regulatory consistency (i.e., whether carbon capture will reduce the carbon payment).

- “Greening” of exports. The growing interest in ESG factors may, at some point, support premiums for exporting green goods versus producing non-green goods. At this stage, these niches are not large enough. However, as buyers of Russian aluminum, steel, pipeline gas or LPG pay more attention to hydrocarbon emissions in their value chain, the demand for such “green” goods may increase.

- Hydrogen. Although Russia has excess electric power generation capacity, it is not yet known whether it will be possible to use it to export hydrogen to Europe. In addition to high transport costs, the fact is that the European hydrogen strategy is aimed at “green” hydrogen obtained with the help of renewable energy sources (which are few in Russia), as opposed to “yellow” and “blue” hydrogen obtained with the help of nuclear power and natural gas (which are in abundance in Russia). The export of methane-hydrogen mixture is technically possible, but in practice, it requires changes in existing contracts and regulations and also affects the technical condition of pipes. However, individual hydrogen projects are still possible: in particular, Rusnano and Enel are working on the possibility of exporting hydrogen produced at the Kola wind farm. The development of the domestic hydrogen market cannot be ruled out either. For example, Rosatom and Russian Railways have announced the launch of a pilot hydrogen-fueled train on Sakhalin. NOVATEK and NLMK have announced their cooperation in the use of hydrogen for the decarbonization of steel production.

- Forestry. Although forests in Russia’s northern climate grow more slowly and absorb less carbon dioxide, there is potential to improve forestry efficiency, for example, by combating forest fires, clarifying accounting issues and collecting information on the ability of Russian ecosystems to absorb carbon dioxide.

Will carbon certificates save Russian exporters?

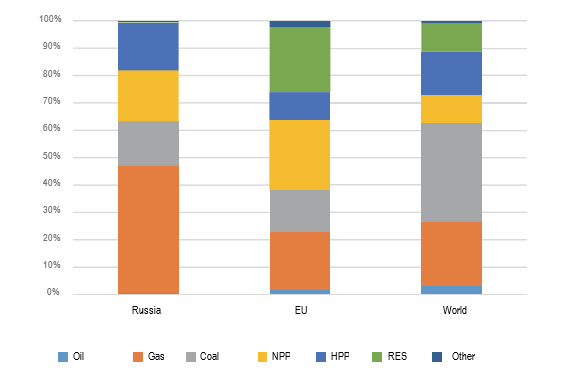

Despite the relatively high average carbon intensity of Russian electricity, low-carbon sources account for a significant part of Russia’s energy balance. Although the national share of renewable energy sources is still significantly lower than the global one (in 2020, they accounted for about 1% of capacity and roughly 0.3% of generation), nuclear and hydro generation accounted for approximately 40% of electricity generation in Russia in 2020.

Currently, Russia is discussing a regulatory framework for the circulation of carbon certificates, which would cover not only renewable energy sources but also nuclear energy and the energy of large hydroelectric power plants. In addition, within the framework of current legislation, companies can enter into direct contracts with electricity suppliers (including carbon-free). There is interest in such contracts: for example, the contract between Polyus and RusHydro covers 90% of the needs of Polyus’ production assets, and Rusal purchases hydroelectric power for its energy-intensive aluminum production. The Russian division of Procter & Gamble has signed a contract with the Wind Energy Fund, a joint venture between Fortum and RDIF. According to our observations, the interest of large Russian enterprises in carbon-free energy is growing.

The current draft of the European Green Taxonomy does not include either nuclear or large-scale hydro generation for reasons related to safety, nuclear waste disposal and impact on biodiversity. However, the carbon footprint of these types of generation is minimal, and inclusion or exclusion in the green taxonomy affects access to financing for new projects rather than the calculation of the carbon levy.

It is not yet known whether direct contracts or carbon certificates for electricity from Russian nuclear power plants and large hydroelectric power plants will be recognized in the European Union. In theory, the output of nuclear power plants and large hydropower plants is likely to be sufficient to meet the demand for carbon-free energy from large exporters as well as other companies seeking to reduce their carbon footprint. In addition to technical issues related to the accounting and distribution of certificates (including distribution between consumers who actually paid part of the cost of carbon-free capacities under the CDA-NPP or CDA-HPP arrangement), a more fundamental problem is that the turnover of carbon certificates and direct contracts themselves do not reduce the carbon footprint of the Russian energy sector, but only redistribute it between the visible (external) and invisible (internal) markets. Thus, certificates don’t help in achieving the goal of reducing emissions, which is contrary to the original meaning of the CBAM. However, this situation is not unique for Russia: in many countries, buying carbon certificates is much cheaper than investing in reducing emissions, which is raising questions and doubts among investors, politicians and environmental activists in many countries.

Carbon footprint is increasingly affecting access to financing

Access to capital and export markets is increasingly dependent on ESG factors, the most measurable of which is the carbon footprint. The issuance of “green” and “sustainable” bonds is growing and the volume of funds under management with ESG strategies is increasing. In its annual message to investors and CEOs, the world’s largest asset manager BlackRock (more than $8.7 trillion under management, including more than $5 trillion in passive funds) warned that it could withdraw the securities of companies that are not fighting against climate change and refusing to disclose the relevant information from its discretionary portfolios. By the end of 2020, more than 3,500 organizations signed the Principles for Sustainable Investment, and 206 banks signed the Principles for Sustainable Banking. These lists are constantly growing.

Russian companies are thus far less susceptible to ESG pressure than international ones, because they initially have less access to cheap financing from foreign markets due to sanctions or country risk. Most of the large rated companies have a relatively moderate leveraged position and are less sensitive to changes in capitalization due to their concentrated ownership structure. However, they are unlikely to be able to avoid ESG pressure from investors. The Russian financial system is not large enough to fully meet the significant financing needs of the largest Russian borrowers. According to our estimates, the maximum amount of a loan to one borrower that the Russian banking system can issue without violating regulatory standards is currently about 2.6 trillion rubles (as of the end of 2020), while the consolidated debt of Gazprom reflected in its IFRS statements as of the end of Q3 2020 is 4.9 trillion rubles. While access to financing within Russia has not – until recently – been overly dependent on climate indicators, this situation is gradually beginning to change. Russian banks still have many carbon-intensive assets on their balance sheets that are hard to find quick replacements for, taking into account the structure of the Russian economy. But some large Russian banks are feeling increasing ESG pressure from their investors and international counterparties, and are beginning to take the appropriate measures. For example, in the new Development Strategy until 2023, Sberbank (35% of the assets of the Russian banking system) indicated that it plans to conduct an ESG assessment of all new corporate loans, bring its corporate purchases 100% in line with ESG principles and create a “green” office.

We believe that in order to maintain access to international financial markets and to adapt to the gradual changes taking place in Russia, companies need to meet investor demand to reduce carbon intensity.

Short-term risk of CBAM – inconsistency of reporting and regulation

In the short term, we see the main risk in the lack of coordination between Russia and the EU in the area of environmental regulation and reporting. Both the Russian and European systems are in the process of development; therefore, dialog is extremely important. Without accounting harmonization, Russian companies may face the risk of a double burden of reporting and carbon payments if Russia decides to introduce them. In addition, if, due to differences in accounting, CBAM is determined on the basis of nominal averages, Russian companies are unlikely to be able to get a return on their investment in reducing emissions.

Finally, improved regulatory engagement will help Russian companies interact with foreign technology partners and gain access to growing new markets for reducing emissions, such as hydrogen markets.

The long-term risk isn’t CBAM, but rather the energy transition

Although in the coming years, Russian exporters are likely to be able to deal with CBAM, the main risks are of a long-term nature and are associated with the structure of the Russian economy and the global energy transition.

The fuel and energy complex accounts for roughly 20% of GDP, no less than a third of the total budget revenues of the enlarged government, and up to 60% of all commodity exports. Replacing these shares won’t be easy. Russian exports to Europe are generally characterized by lower added value in comparison with countries such as China, making them more sensitive to CBAM. We do not expect significant growth in economic diversification in the coming years. Over the long term, the energy transition and growing ESG pressure from investors increase the risks of the oil and gas industry around the world. Given the decline in investments in the oil and gas sector (by 30% in 2020, according to IEA estimates), national companies with large reserves, low costs and relatively less ESG pressure from investors and regulators are now in the best position to remain profitable – even in a falling market. That’s why in January-February 2021, we downgraded the credit ratings of a number of major global oil and gas companies (including Exxon, Shell, Chevron, etc.) and affirmed the ratings of the largest Russian companies – Gazprom, LUKOIL, Rosneft, NOVATEK. However, the energy transition and the high volatility of energy prices observed in 2020 increase the risks for them as well. In the long term, the question of how the declining rents from fossil fuel extraction will be distributed among the government, infrastructure companies and the largest producers will become more acute.

In the future, the difference in carbon intensity between Russian and foreign companies will grow. Many countries, including not only the European Union but also China, South Korea and Japan, have set goals to achieve net zero emissions. Although the feasibility of some decarbonization plans raises doubts due to the vagueness of the list of specific technical measures, there is obvious public demand for engineers and manufacturers to reduce emissions. The goal of reducing emissions to 70% of the 1990 level, set by Decree No. 666 of the President of the Russian Federation in November 2020, taking into account the absorptive capacity of forests, is very realistic (in fact – it has already been achieved) but hardly ambitious.

Reducing carbon intensity is gradually becoming an important factor in competitiveness on the global market, not only because it reduces carbon payments, but also because it helps companies integrate into international production chains, gain and maintain access to markets, technologies and financing.